You may not know this about me, but I am sort of obsessed with Eminem. He’s one of the most intelligent rappers making music right now, and his verses routinely juxtapose the profound and the profane, making him one of the more provocative artists working right now.

You may not know this about me, but I am sort of obsessed with Eminem. He’s one of the most intelligent rappers making music right now, and his verses routinely juxtapose the profound and the profane, making him one of the more provocative artists working right now.

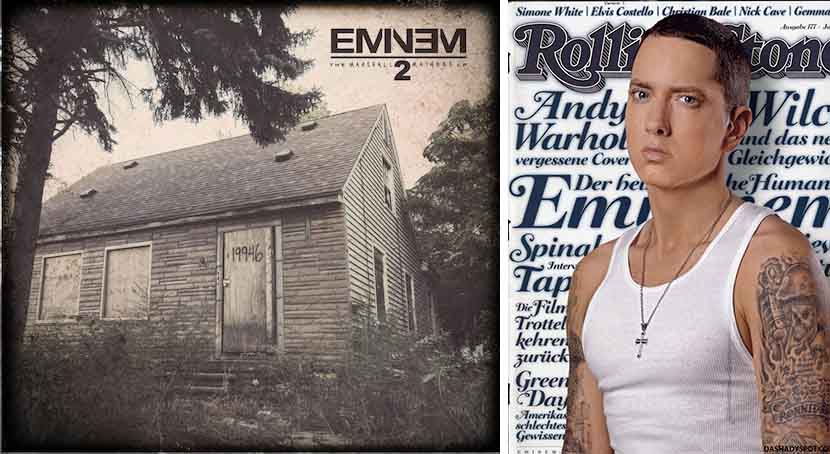

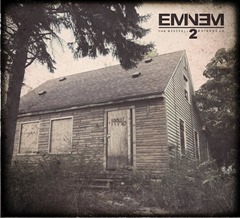

Eminem’s newest release – the Marshall Mathers LP2 – is no exception. It sold 800,000 in its first week and is easily the fastest- and biggest-selling hip-hop album this year – a year that includes new Kanye, Jay-Z and Drake releases. And as you’d expect, MMLP2 is every bit as divisive as his previous albums.

Eminem is a major voice in our culture. Love him or hate him – or love him and hate him like I do, we’d do well to pay attention to what Eminem has to say.

Each of the first three singles on MMLP2 is generating its own buzz – “Berserk” for its callback to classic hip-hop, “Monster” for its made-for-radio-plus-Rihanna goodness. And then there’s “Rap God”, featuring a mediocre hook and six-plus minutes of blisteringly fast rap. Eminem spits over 1,500 words in “Rap God” – it’s fully half as long as the average sermon I write.

“Rap God” has all the hallmarks of a classic Eminem song – it’s witty, stuffed with punch-lines and lightning quick. It’s also vulgar, crude and violent. According to the lyrics, the sole purpose of “Rap God” is to prove that Eminem is the best rapper in the game, and judging by the reactions to the song, he’s accomplished his mission.

Even those who hate the song begrudging admit the skill on display in the song is unparalleled. It’s no coincidence, then, that Eminem muses that he’s “beginning to feel like a Rap God”.

The lyrics of the song are augmented by the newly-released video (above) that features snippets of biblical-looking text, shots of apocalyptic Albrecht Durer carvings, and Marshall himself walking on water. Subtle, right?

“Rap God” demonstrates a particular view of deity – and therefore power – at odds with Jesus’ model of godhood.

Toward the end of the song, Eminem mocks those rappers who can’t keep up with him (e.g., everyone else) by asking

How many verses I gotta murder to prove that if you were half as nice at songs, you could sacrifice virgins too?

Eminem’s particular understanding of power is clear: he can say and do whatever he want because he’s so much better than everyone else. He can be as violent, as homophobic, as crass as he cares to be and he will still sell records because he’s the best there is. His unparalleled talent place him above morality, beyond right and wrong. Other rappers may need to watch what they say, avoid offense or offer positive verses if they want to sell. But not him.

In “Rap God”, Eminem defines godhood as the ability to do whatever you want. In other words, might makes right.

It’s hard to argue with his logic. In several tracks on MMLP2, he acknowledges that he’s as crass as he ever was, that twenty years in the rap game have done nothing to mature or tame him. And yet the record is easily the best-selling of the year, and Eminem’s most successful record in years.

It’s hard to argue with his logic. In several tracks on MMLP2, he acknowledges that he’s as crass as he ever was, that twenty years in the rap game have done nothing to mature or tame him. And yet the record is easily the best-selling of the year, and Eminem’s most successful record in years.

Ironically, a large segment of American Evangelicalism agrees with Eminem. The New Calvinism movement (popularized by pastors like John Piper and Mark Driscoll) is captivated by what they define as God’s “sovereignty” – God’s absolute power over all creation. For these Christians, what makes God the god is his supreme and unquestioned power over all.

Whether declaring that God was “delighted” to slaughter women and children celebrating not the Jesus who bleeds for his enemies, but a Jesus who can’t wait to bleed his enemies dry, these pastors celebrate God’s transcendence. And this transcendence explicitly includes transcendence over morality. For these preachers, what makes God god is his unchallengeable ability to do whatever he wants. For them, God’s might makes God right.

And yet Jesus’ definition and demonstration of power and godhood could not be more opposite.

When the disciples argue over position and authority in Mark 10, Jesus warns them that in his kingdom, the last shall be first, because even he did not come to be served, but to serve.

When the disciples argue over position and authority in Mark 10, Jesus warns them that in his kingdom, the last shall be first, because even he did not come to be served, but to serve.

The night he was betrayed, he stripped down to nothing, assumed the posture of a slave, and washed the feet of all his followers – even Judas who was hours away from betraying him.

An early Christian hymn found in Philippians 2 celebrates that Jesus didn’t use his position to assert authority, but gave it away to all of us, used what he had to lift others up, not tear them down or lift himself up.

And Jesus’ speech to Nicodemus makes it clear that none of this is an accident, or incidental. Jesus’ self-sacrifice is how he is glorified. Jesus is lifted up when he is lifted up on the cross. In the upside-down kingdom of God, death is victory, and the death of the one brings life for all.

Jesus isn’t God despite the fact that he died, he is God because he died. In other words, Jesus’ death shows us what kind of God he is.

Nothing could be further from Eminem’s vision of godhood and power we learn in “Rap God”. Then again, I don’t listen to Eminem expecting to hear good theology. Clever lyrics? Yes. Incisive critiques of American culture? Definitely. But good theology? No.

Nothing could be further from Eminem’s vision of godhood and power we learn in “Rap God”. Then again, I don’t listen to Eminem expecting to hear good theology. Clever lyrics? Yes. Incisive critiques of American culture? Definitely. But good theology? No.

(Anyway, Eminem acknowledges as much in “Rap God” when he asks, “Satan, take the wheel.” He’s under no illusions that what he’s doing is Jesus-like. But that observation deserves its own post!)

God is not god because God is more powerful than we are. Superman is more powerful than we are. Okay, Superman is fake. Arnold Schwarzenegger is more powerful than I am in pretty much every way – physically, politically, etc. What makes God god – what makes God’s way the way to life – is how God uses the power God has.

So too, what makes us great is not how far our abilities elevate us above our peers (competition?) but how well we use those abilities to serve even those we count as enemies.

Should we expect that from rap songs? Probably not – at least not in the mainstream (though there are a few good Christian rappers, and underground hip-hop remains largely positive). But we ought to put our foot down, to refuse any theology that paints God so fundamentally at odds with who we see revealed in the person of Jesus. I’ll tolerate it from Eminem. I’m not interested in hearing it from those who claim to speak for Jesus.