A chronicle of my trip to Jerusalem, Cairo and Rome from November 3-18. If you want more information on a picture, hover your mouse over it for a pop-up caption. If you want to see a bigger version of the picture, click on it.

The picture above is a representation of Jerusalem how it would’ve looked in Jesus’ day. The large stone complex to the left is the Temple Mount (the Temple itself is the gold-topped structure just visible over the top of the towers in front of it). Trace the route of the city walls: they run in front of the Temple complex to the Damascus Gate (just to the right of halfway in the picture). Then they run straight back before again continuing across. Herod’s palace is visible in the far back right.

If you look closely where the wall hooks, you can see that it did so to avoid a large pile of rock. This was a old rock quarry that had fallen out of use. One piece of rock was formed of harder mineral than the stuff around it, so it was left jutting up out of the ground. Around it were quite a few caves that were sold off to be used as tombs (allowed since the whole thing was outside the city).

If you look closely where the wall hooks, you can see that it did so to avoid a large pile of rock. This was a old rock quarry that had fallen out of use. One piece of rock was formed of harder mineral than the stuff around it, so it was left jutting up out of the ground. Around it were quite a few caves that were sold off to be used as tombs (allowed since the whole thing was outside the city).

That rock that’s sticking up is Golgotha, the Place of the Skull, Calvary – where Jesus was crucified. And Joseph of Arimathaea had purchased one of those tombs, which is where he had Jesus buried. Today, the whole thing is inside the Old City, and it’s all inside the same church building – the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The Temple is gone and replaced by the Dome on the Rock, but you can still get a sense of how close everything is.

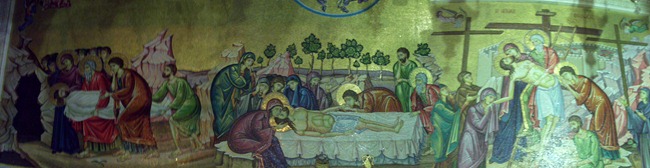

In the long and sordid history of the Holy Land, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher has been through a lot, but inside you can still see (and touch) the rock formation of Golgotha, as well as enter into a large structure that has been built around the remains of the Tomb. The Tomb stood in the Church for quite some time – the other tombs having all been carved away when the building was erected, but it was leveled by the Caliph who conquered Jerusalem in the 1000s. All that’s left is a raised area revealing where Jesus’ body would’ve laid, which has now been converted into an altar from which Mass is said.

Because Thomas is a priest, he was able to arrange for us to say Mass in the Tomb twice – on Wednesday and Thursday mornings (November 10-11).

Mass on Wednesday was quite an experience. We were to begin Mass at 5:00 am, so we got up very early while it was still dark and made our way to the Old City. But we got lost and began to be afraid that we would miss our Mass time. We ended up sprinting through the Old City – dark, quite and abandoned at this time of morning, unable to find the entrance to the Church.

Mass on Wednesday was quite an experience. We were to begin Mass at 5:00 am, so we got up very early while it was still dark and made our way to the Old City. But we got lost and began to be afraid that we would miss our Mass time. We ended up sprinting through the Old City – dark, quite and abandoned at this time of morning, unable to find the entrance to the Church.

With literally minutes to spare, we finally found our way in and hurriedly made our way into the Tomb, flanked by two sisters (the Tomb accommodates four, so I can only assume that if your party isn’t full, they fill it with random clergy). At the last minute, an Asian-American priest leading a larger group of parishioners invited his group into the Tomb’s antechamber to celebrate the Mass with us.

So at 5:00 in the morning on Wednesday, I said the Mass of the Resurrection kneeling at the altar with Thomas, two nuns (at least one of whom I’m pretty sure was Spanish) and a large group of Asian-American pilgrims.

So at 5:00 in the morning on Wednesday, I said the Mass of the Resurrection kneeling at the altar with Thomas, two nuns (at least one of whom I’m pretty sure was Spanish) and a large group of Asian-American pilgrims.

Thursday morning, since our Mass didn’t begin until 7:15, we were joined by Father Kevin and Nina, a German student at the School. The experience was dramatically different: we walked there, arrived in plenty of time, and Nina and I were able to catch the end of the larger Mass being sung before our turn, while Thomas and Kevin got suited up. Our time in the Tomb itself was relaxed and solemn. I was struck for the first time by how thoroughly the Mass is permeated with the proclamation of the peace Jesus brings to us.

Of course, since I am not Catholic, I was not permitted to take part in the Eucharist (Communion) Meal at the end of Mass. This is something both Thomas and I greatly regret, and it cast a pallor over the events for me (Thomas was very gracious to me, inviting me to perform the Scripture readings both days). While I continue to wrestle with my exact theology concerning the Communion meal, I believe at least that all Christians should participate together. I have many good friends who are Catholic, and it saddens me that we cannot share in our most sacred ritual together.

Of course, since I am not Catholic, I was not permitted to take part in the Eucharist (Communion) Meal at the end of Mass. This is something both Thomas and I greatly regret, and it cast a pallor over the events for me (Thomas was very gracious to me, inviting me to perform the Scripture readings both days). While I continue to wrestle with my exact theology concerning the Communion meal, I believe at least that all Christians should participate together. I have many good friends who are Catholic, and it saddens me that we cannot share in our most sacred ritual together.

But what really troubled me was that the Church – supposedly the most holy site on Earth – is in practice a shrine more to our own human frailty than God’s majesty. Jerome Murphy-O’Conner says it well in his guide to the Holy Land:

One expects the central shrine of Christendom to stand out in majestic isolation, but anonymous buildings cling to it like barnacles. One looks for numinous light, but it is dark and cramped. One hopes for peace, but the ear is assailed by a cacophony of warring chants. One desires holiness, only to encounter a jealous possessiveness: the six groups of occupants – Latin Catholics, Greek Orthodox, Armenian Orthodox, Syrians, Copts, Ethiopians – watch one another suspiciously for any infringement of rights. The frailty of humanity is nowhere more apparent than here; it epitomizes the human condition.

Six different Christian groups hold rights to some part of the building, and they can’t agree on anything. Even repairs to keep the building from falling down were only agreed to after lengthy discussion and debate. Back in the 1800s, the Ottoman Empire got tired of all the groups arguing and forced them to come to an agreement that became known as the Status Quo that regulates everything from who controls what part to Mass schedules in the Tomb itself. A Franciscan friar told us that the Status Quo is taken so seriously that if one group leaves trash in their section of the Church and another group picks it up, that section of the Church comes under the control of the group that cleaned (because they did work in that area). Thus each group carefully polices ‘their turf’ in order to protect their interests.

This whole absurdity has come to be symbolized by a rather peculiar piece of furniture: outside the front of the Church, there’s a ladder that leads from a second-story window to a sort of fire-escape. The ladder’s been there since the implementation of the Status Quo, and two explanations for its existence abound. I’ll leave it for you to decide which is sadder:

-

The ladder is actually a fire escape. (This next part we know for certain:) Because none of the Christian groups could trust each other with the keys to the Church – one group was locked out for quite some time at one point – they all agreed clear back in the 600s to give the keys to a Muslim family, who locks the door at 7:00 each night and unlocks it around 4:30 every morning. Thus anyone in the building after 7:00 pm is locked in. Because of this, Christians do not celebrate an Easter vigil the Saturday of Easter weekend in the Tomb where Jesus rose from the dead.

The Church of the Holy Sepulcher is a maddening array of contradiction. It’s beautiful, sacred and powerful, yet also a chaotic, divided mess. It truly does embody the fullness of the tension we live between the Cross and the empty Tomb. I can’t wait for the day we experience the full power of the resurrection and all share in communion together.