The Beard Goes Home is an ongoing chronicle of my trip to Israel, Cairo and Rome from November 3-18. If you want more information on a picture, hover your mouse over it for a pop-up caption. If you want to see a bigger version of the picture, click on it.

After saying Mass in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher on the morning of Thursday, November 11, Thomas and I picked up our rental car and left Jerusalem. After getting turned around only once, we headed East and South, towards the Dead Sea and Masada. The transformation of the countryside was immediately evident as we quickly entered the Judean Desert. Any trace of greenery vanished and we were left with large, brown hills sloping endlessly away in all directions.

After saying Mass in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher on the morning of Thursday, November 11, Thomas and I picked up our rental car and left Jerusalem. After getting turned around only once, we headed East and South, towards the Dead Sea and Masada. The transformation of the countryside was immediately evident as we quickly entered the Judean Desert. Any trace of greenery vanished and we were left with large, brown hills sloping endlessly away in all directions.

We turned and headed south at the tip of the Dead Sea, and it wasn’t long before the Sea fell away before us on our left while the caves of Qumran – where the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered – loomed high on our right.

In almost no time at all, we reached Masada, a mesa rising out of the Judean Desert surrounded by nothing and looking out over what was once known as the Devil’s Sea. It feels like the loneliest place on the whole planet.

History of Masada

Masada was originally the site of one of Herod the Great’s palaces, built as a sort of ‘last resort’ in case things got really bad for him. It’s grotesquely inaccessible, but Herod managed to deck the whole top of the mesa out with nothing but the best, including two palaces, a full swimming pool (in addition to public and private baths), three small ‘guest palaces’ and of course two full fortresses. He also devised an ingenious system for delivering water up to Masada, so that the whole complex could be endlessly self-sufficient.

After Herod’s death, Masada was basically abandoned for 70 years. During that time, Rome increased their hold on Israel until in 66 CE, rebellion broke out. This First Jewish War (66-73 CE) brought the complete destruction of Jerusalem and the Second Temple (70 CE) and was a major turning point in the history of both Judaism and Christianity.

After Herod’s death, Masada was basically abandoned for 70 years. During that time, Rome increased their hold on Israel until in 66 CE, rebellion broke out. This First Jewish War (66-73 CE) brought the complete destruction of Jerusalem and the Second Temple (70 CE) and was a major turning point in the history of both Judaism and Christianity.

Battles were fought all over Israel (including on Mt. Megiddo, which we’ll see on Saturday), but the Jewish Rebels’ last stand was here at Masada. The rebels climbed the mesa and dug in as the might of Flavius’ Roman army spread around them. The siege lasted three months, during which time the Romans constructed a ramp that allowed them to break down the walls of Masada. On April In a fierce battle, the Romans breached the walls of Masada near the end of the day; because it was so late, and because victory was now assured, the Romans broke for the night, intent on finishing off the Jews the following day.

That night, the Jewish rebels made a terrible decision: rather than face certain defeat and enslavement, they would kill themselves and their families. They set fire to the store rooms and killed themselves. When the Romans came onto the mesa the next morning, they were greeted only by corpses. In the wake of the mass suicide, Masada was abandoned for nearly 2,000 years.

That night, the Jewish rebels made a terrible decision: rather than face certain defeat and enslavement, they would kill themselves and their families. They set fire to the store rooms and killed themselves. When the Romans came onto the mesa the next morning, they were greeted only by corpses. In the wake of the mass suicide, Masada was abandoned for nearly 2,000 years.

The Masada Shall Never Fall Again

Until the mid-1800s, we knew about Masada only through Josephus (a Jewish writer from just after Jesus’ time). But archaeologists located Masada and began to excavate it, and it quickly became a pilgrimage site for Jews from around the world (remember that this was about 100 years before the state of Israel would exist).

Until the mid-1800s, we knew about Masada only through Josephus (a Jewish writer from just after Jesus’ time). But archaeologists located Masada and began to excavate it, and it quickly became a pilgrimage site for Jews from around the world (remember that this was about 100 years before the state of Israel would exist).

Today Masada has entered into the popular Jewish cultural imagination. They speak of a ‘Masada-complex’, which is basically a ‘you’ll-have-to-kill-me-first’ mentality. Some divisions of the Jewish Defense League are sworn in on Masada, with the phrase, “The Masada shall never fall again” included in their oath.

What struck me most about the Masada was how little connection I have to it. It doesn’t play an important role in my history, and as a non-Israeli, I relate to the story of the Jews there less even than I do to the story of the Alamo (because I’m not Texan, either). The introductory film presentation and all the literature (maps and signage) make it very clear, however, that Masada is a vital piece of the Israeli identity.

What struck me most about the Masada was how little connection I have to it. It doesn’t play an important role in my history, and as a non-Israeli, I relate to the story of the Jews there less even than I do to the story of the Alamo (because I’m not Texan, either). The introductory film presentation and all the literature (maps and signage) make it very clear, however, that Masada is a vital piece of the Israeli identity.

The story that’s told is one of Jews who would rather die free than live as slaves. And as rhetoric goes, it’s great stuff. But that’s not really the whole story. The Jews weren’t just any Jewish rebels. They were Sicarii – a radical splinter group who had broken off from the Zealots (who were already pretty radical) because they weren’t radical enough. The Jews at Masada were not typical first century Jews. They were a fringe movement, lead by a charismatic (but probably slightly unstable, as leaders of these movements tend to be) guy who, when the chips were down chose the easy way out. I couldn’t help but think of Jonestown (where, granted, the CIA threat was much more imaginary than the Roman Empire).

Remembering Masada Well

I think what disturbs me about Masada is that what happened there was not the result of normal, everyday persons put into extraordinary circumstances. The Sicarii were fringe revolutionaries. But because of the way we are now reimagining their stories, their response to a cause that seems overwhelming and insurmountable has become laudable. What’s working into the Israeli psyche (and that of any visitor to Masada) is that the most courageous response to overwhelming violence is a stubborn refusal to compromise and bitter acquiescence and passivity.

I think what disturbs me about Masada is that what happened there was not the result of normal, everyday persons put into extraordinary circumstances. The Sicarii were fringe revolutionaries. But because of the way we are now reimagining their stories, their response to a cause that seems overwhelming and insurmountable has become laudable. What’s working into the Israeli psyche (and that of any visitor to Masada) is that the most courageous response to overwhelming violence is a stubborn refusal to compromise and bitter acquiescence and passivity.

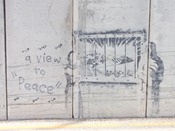

This cannot be true. We must never give up pursuing peace. Masada ought to be a reminder of the dangers of following zealots. A lesson that meeting overwhelming force with force only ends badly. That if we want something better than death, we’d better get more creative. Masada ought to be a tragedy, not an inspiration.*

*Of course, I’m the comfortable American who says this not having been a part of a people without a land for 2,000 years. In that way, it’s impossible for me to know fully what Masada means to the Jewish people. But I do not believe that remembering a glorified, sterilized Masada is helpful or redemptive.

Some Christians see Israel’s modern state as the fulfillment of prophecy. Others feel the opposite. Both sides caricature the other. Far from Peacemaking, many Christians only fuel the conflict.

Some Christians see Israel’s modern state as the fulfillment of prophecy. Others feel the opposite. Both sides caricature the other. Far from Peacemaking, many Christians only fuel the conflict.